Image Sequence Formats – the challenge of collaborating on millions of files

From Flipbooks to Film

You probably remember making flipbooks. If you were like me, you realized that they were a great way to entertain yourself during that boring junior high history class. But you probably didn’t realize that the flipbook was an important precursor to the modern film industry.

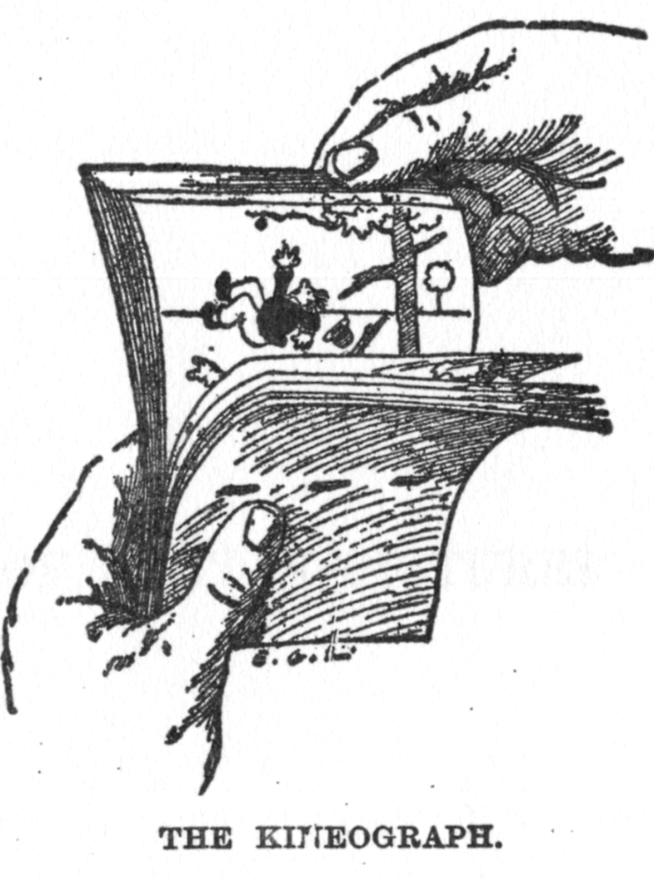

The first flipbook was patented by John Barnes Linnett in 1868; he called his invention a kineograph (Latin for “moving picture”). Unlike its predecessors, his was the first form of animation to use linear image sequences instead of image sequences affixed to the inside or outside of circular drums.

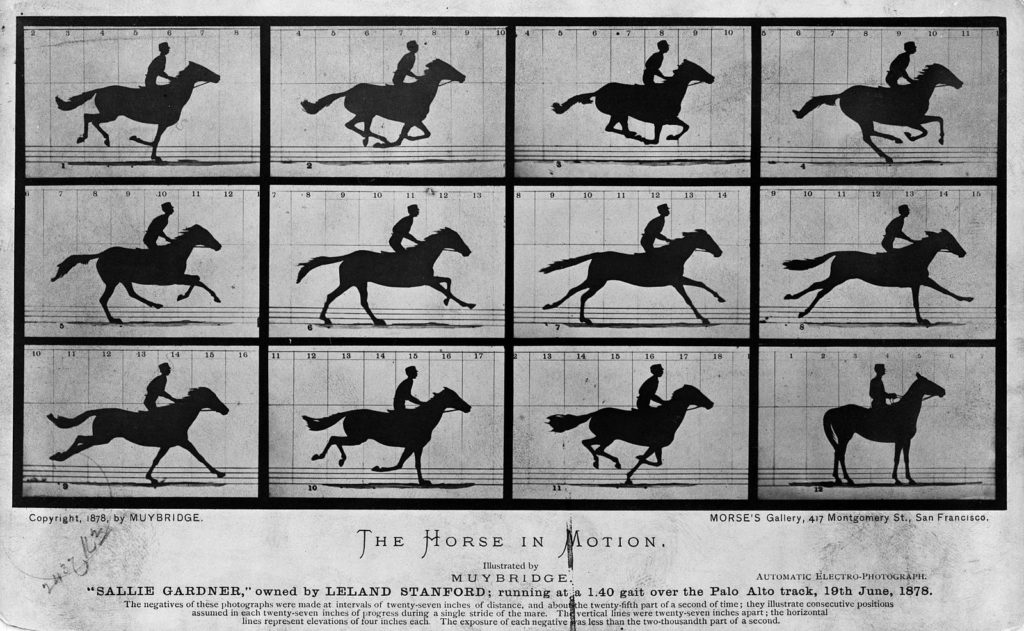

Another important development occurred in 1872 when Edward Muybridge, a renowned nature photographer, used an array of cameras to capture an image sequence of a trotting horse to prove that all 4 hooves are off the ground at the same time. The Muybridge zoopraxiscope enabled the image sequences he produced to be projected and is considered to be the forerunner of the modern film projector.

The 1880’s saw the development of cellulose movie film and the first practical movie cameras appeared just after 1890. Together, they enabled photographers to capture a series of still photographs of a scene.

Movies are the result of projecting this sequence of images in rapid succession to produce the illusion of smooth continuous movement. The combination of film-based movie cameras and projectors formed the basis for the movie industry ever since.

From Film to Files

Digital technology has impacted the film industry in many ways. Film scanners are sophisticated imaging devices that convert film images to digital files with each file representing one (and only one) film frame. Files are almost always output in DPX format, though you may occasionally encounter CINEON, TIFF or other formats. These file formats are favored due to their ability to preserve the raw high color depth and resolution of film stock.

Digital technology has also enabled great leaps in the visual special effects (VFX) capabilities of the film industry. Powerful computers and VFX software enable film makers to create environments, inanimate objects, animals and/or creatures which look realistic, but would be dangerous, expensive, impractical, time consuming or impossible to capture on film.

VFX workflows rely upon image sequences with file formats like EXR (a.k.a. Open EXR) is popular, as is DPX, TARGA, TIFF and PNG mainly for their high resolution but also so that, if a render job crashes, (more common than you might think) frames already rendered aren’t lost to the reboot.

Thanks to the emergence of high resolution (4K and above) digital cameras that can achieve the same resolution, color depth and behaviors as film cameras, Digital Cinema cameras are now common in modern film production. Because they output digital files rather than film, filmmakers can avoid the expense and logistics of developing the exposed film and quickly deliver files for review and the start of post-production. Digital Cinema cameras typically output either proprietary RAW files (ARRIRAW, R3D require conversion to file-per-frame format like DPX) or compressed video files like ProRes and DNxHD that can be used as is for editorial purposed.

Customer challenges when using image sequence files

File size – a DPX file containing a single frame of 10-bit HD (1920 x 1080 pixels) will be approximately 8 MB in size. A DPX file containing a single frame of 10-bit 4K (4096 x 2304 pixels) will be approximately 36 MB in size. Be aware, depending on where in the workflow the customer is, DPX files as large as 50 MB per frame due to the use of non-standard aspect ratios, incorporation of an alpha (auxiliary info) channel, and higher 16-bit color depth.

Number of files – A 108-minute feature film, like Deadpool has 155,000 video frames; imagine having to manage or move 155,000 high-resolution files.

Image sequence files are usually managed within a hierarchical file system structure and are stored as folders containing multiple image sequence files. When collaborating in these formats, especially across locations and companies, new challenges arise. Sharing a folder with tens of thousands of files, each in sequence that must be delivered from a source folder arrive at the destination folder without degradation is something most standard tools aren’t capable of. Clearly, the size of image sequence files means that whenever workflow requires file movement, the payload is significant. For example, a 90-minute feature film in 10-bit HD DPX format produces a payload in excess of 1 TB. A 4K version is in excess of 4 TB. Signiant is well known for moving large files with speed and reliability but our products also make it easy to move formats that include huge numbers of images.

Learn more about how Media Shuttle and Jet can make it easy, fast and reliable to collaborate on DPX, EXR and other formats where tens of thousands of images (or more) need to be shared.